Fall of 2022, a few high school students came together, unfiied by the idea to form a rocketry team. We started small: 8 students across 2 grades with a few monthly meetings, learning about different types of propellants, recovery deployments, pyrotechnics, and avionics systems. Fastforward to March, we managed two nominal small-rocket launches at our local Winston Churchill Park, and thus became the Bishop Strachan Rocketry Team (BSRT).

One year later, we began reaching for greater heights. Having built a solid foundation in rocketry basics and recruiting a few more students, we set our sights on competing at Launch Canada 2024 — the premier Canadian high-power rocketry competition for university design teams. If approved, we would be the first high school team and the only all-female team to ever compete at Launch Canada. On paper, that was exciting. We didn’t bother with doubts or second-guesses. We just got to work.

After being accepted to compete, our team of 12 split into sub-teams: airframe, payload, recovery, and avionics. Each group was responsible for designing, building, and testing their respective systems — all while ensuring integration with the overall rocket.

Typically, most Launch Canada teams have ~12 members per sub-team. Given our size, everyone wore multiple hats. I was the avionics lead, but I was also deeply involved in payload integration, recovery system checks, and especially the full assembly of our SRAD carbon fiber airframe.

In reality, the sub-team structure was more aspirational than rigid. With only 12 people, no one ever truly stayed in their lane. On any given day, airframe members were learning avionics wiring, payload members were sanding couplers, and recovery checks turned into full-system integration reviews.

This wasn’t a flaw in our team — it was a necessity. When something needed to be done, whoever was there did it. That meant learning quickly, asking questions without ego, and being willing to take responsibility for systems you hadn’t originally “owned.”

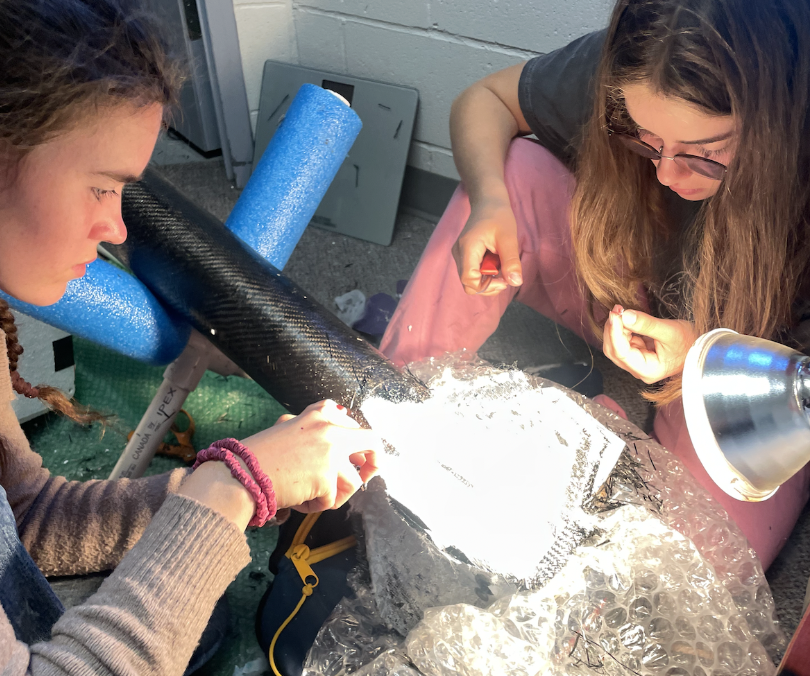

While I formally led avionics and co-led payload integration, I also assisted with recovery system layout, and most of all, the hands-on assembly of our SRAD carbon fiber airframe. It was the first time I really understood how intertwined rocket systems are: avionics doesn't exist without structure, recovery doesn't work without clean wiring, and payloads don't fly unless everything else does.

At competition

In August of 2024, we arrived at Launch Canada — suddenly surrounded by university teams with years of experience, custom tooling, and institutional knowledge. We were the youngest team on the field, and the only one made up entirely of women.

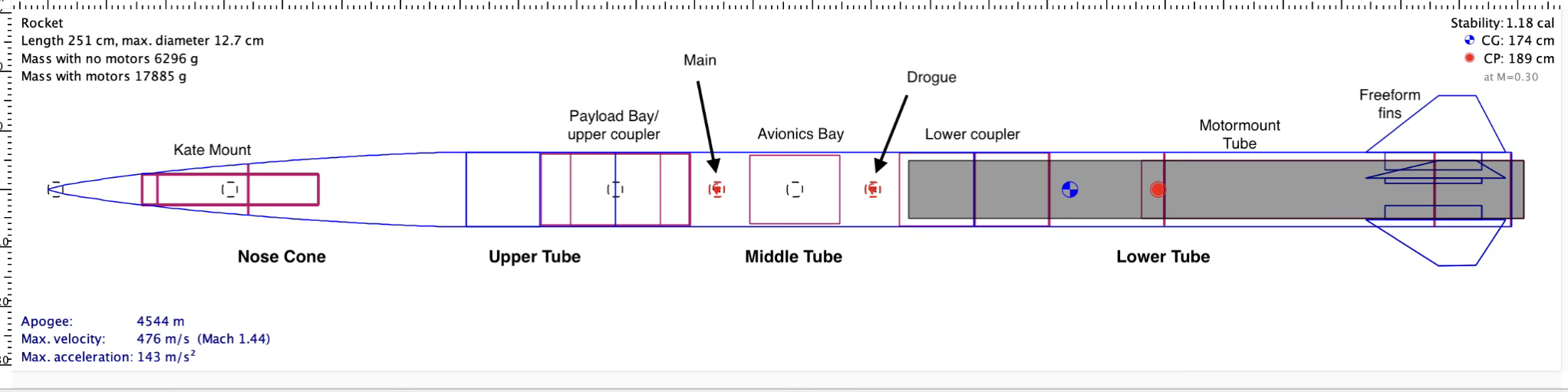

The payload project I co-led was a 3D-printed pressure vessel designed to test hydrostatic pressure under high gravitational force, and we integrated double-redunancy blue-raven altimeters for our COTS avionics system coupled with black powder charges for pyrotechnic deployment.

Our rocket was designed to reach approximately 16,000 feet, entering the supersonic regime shortly after leaving the rail. Yet, after various inspections and by the end of the third day, we were told our rocket had too many flight-critical issues to launch.

That moment was devastating....

Luckily, we had 3 days to make it right.

Stepping up

Faced with the possibility of not flying at all, I took responsibility for finding a way forward. I spoke directly with a safety officer to understand which issues were non-negotiable, which could be mitigated, and which required immediate redesign.

To free up my teammates to focus on structural and mechanical problems, I took it upon myself to troubleshoot and repair all of our flight computers. This meant opening commercial avionics systems, understanding their logic, reworking wiring, and validating functionality under time pressure.

In doing so, I realized something unexpected: commercial avionics for amateur rocketry aren’t as opaque or magical as they seem. They are thoughtfully engineered — but understandable. Particularly with my background and comfort with computer science, it became of interest to me to engineer my own sometime down the line, and was the start of my journey into avionics and controls.

Outside of avionics, I assisted with the tip-to-tip fin layup, where the University of Toronto Aerospace Team (UTAT) generously supported us by lending slow-cure epoxy and sharing their experience. Working alongside them, watching their hybrid rocket prep for a record-breaking altitude attempt, was deeply inspiring.

By the final day before our last launch window, we had addressed

every major flight-critical concern. Our avionics were rewired and tested,

our recovery systems double-checked, and our airframe inspected.

We were ready to fly!

The final window

Against the odds, we had resolved all major flight-critical concerns.

As we drove to the launch pad, relief finally set in. As I had used the telemetry system before during summer tests, I was assigned to monitor the live data stream during flight, and went up to the observation tower to set up.

Then, in a moment that still replays vividly in my head, the rail attachment button struck the rail and snapped off. The issue here was subtle but critical: upon a few last minute decisions, our team decided on a minimum-diameter-rocket (MDR) design, which meant that the rail button was only millimeters away from the rail itself. During launch, the slight misalignment caused the button to strike the rail, snapping it off entirely.

There was no safe workaround. No last-minute fix. Launching would have been irresponsible.

We packed up in silence.

What stayed with me

Despite the heartbreak, Launch Canada 2024 left me with something far more lasting than a flight: a burning curiosity about avionics.

Fast forward to now (2025!), and I have designed, implemented, and coded a custom avionics system, which will be tested at Tripoli in mid-July before we return to Launch Canada for our second year. Furthermore, our team's last-minute adversity and crunch-time problem solving was truly inspiring and has shaped how I approach engineering challenges today. A few jokes got tossed our way amidst commendments during closing ceremonies regarding how BSRT had just experienced true engineering, but you've got to admit — nothing hones your skills like a last-minute crisis. Our final submission still counted towards the competition as we did submit our designs and reports, and learned that sometimes, flying isn't just about piercing those clouds. I'm so grateful for the people I've had the pleasure of working with amidst this insane venture, and I can't wait to see where rocketry takes us next.

We didn’t launch in 2024.

But that experience shaped exactly how we'll fly in 2025.