There is something incredibly satisfying about physical hardware. Writing code that runs in a browser is fine, but writing code that runs on a Raspberry Pi inside a custom-built cabinet with arcade buttons? Way cooler.

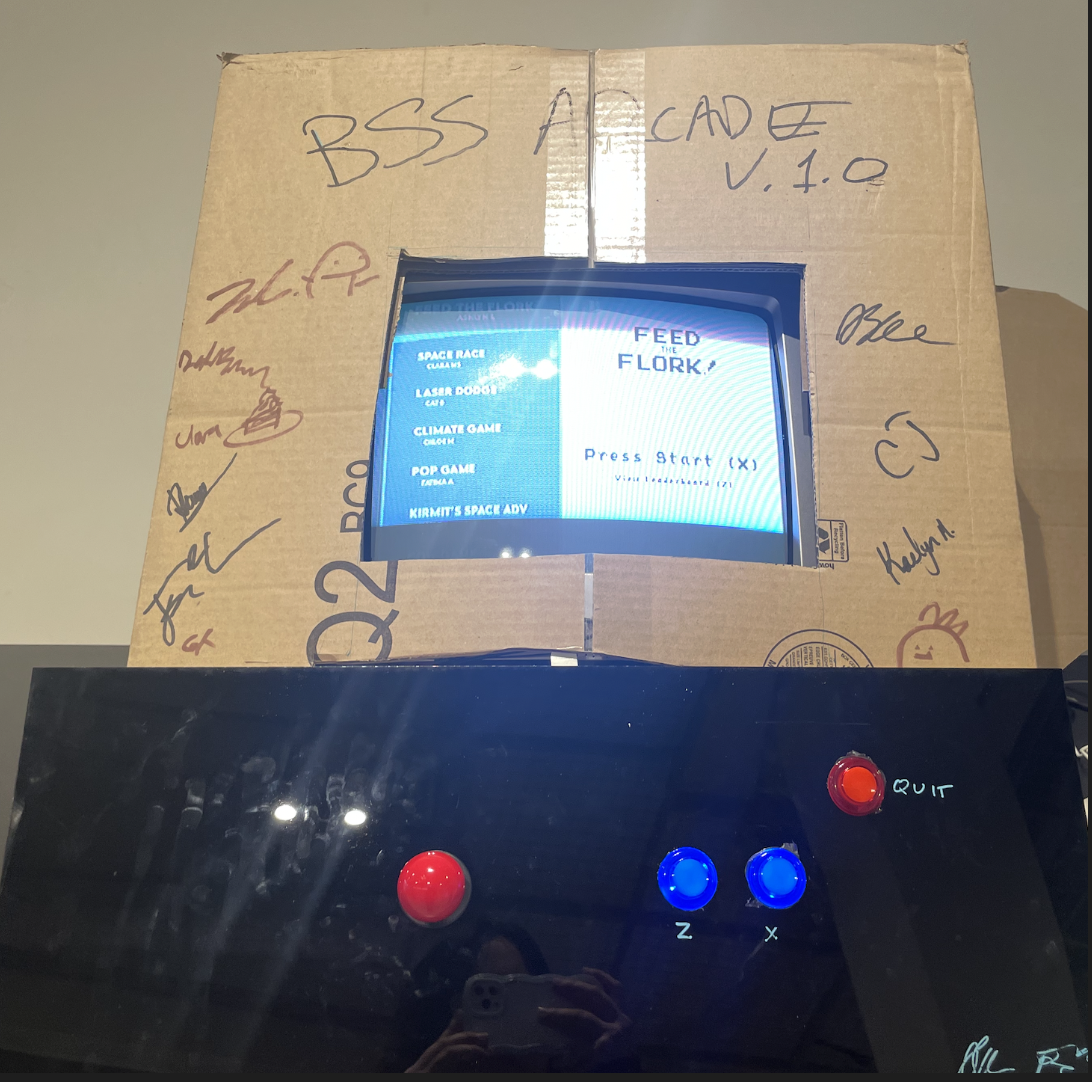

This is the BSS Arcade Cabinet—a dedicated launcher and database system designed to preserve and play ICS3U student games from 2022 onwards.

The Stack

The heart of the system isn't a modern engine like Unity; it's Processing 4, which is what most of the course is taught within. So, along with coding my video game, I built a custom launcher interface that reads from an SQLite database to track game metadata (title, author, description, high scores) and allows users to select and launch games directly from the arcade cabinet!

- Core Engine: Processing 4 (Java)

- Database: SQLite (via SqliteDebier) to track game history and metadata.

- Hardware: Raspberry Pi with custom GPIO mapping.

Hardware Integration

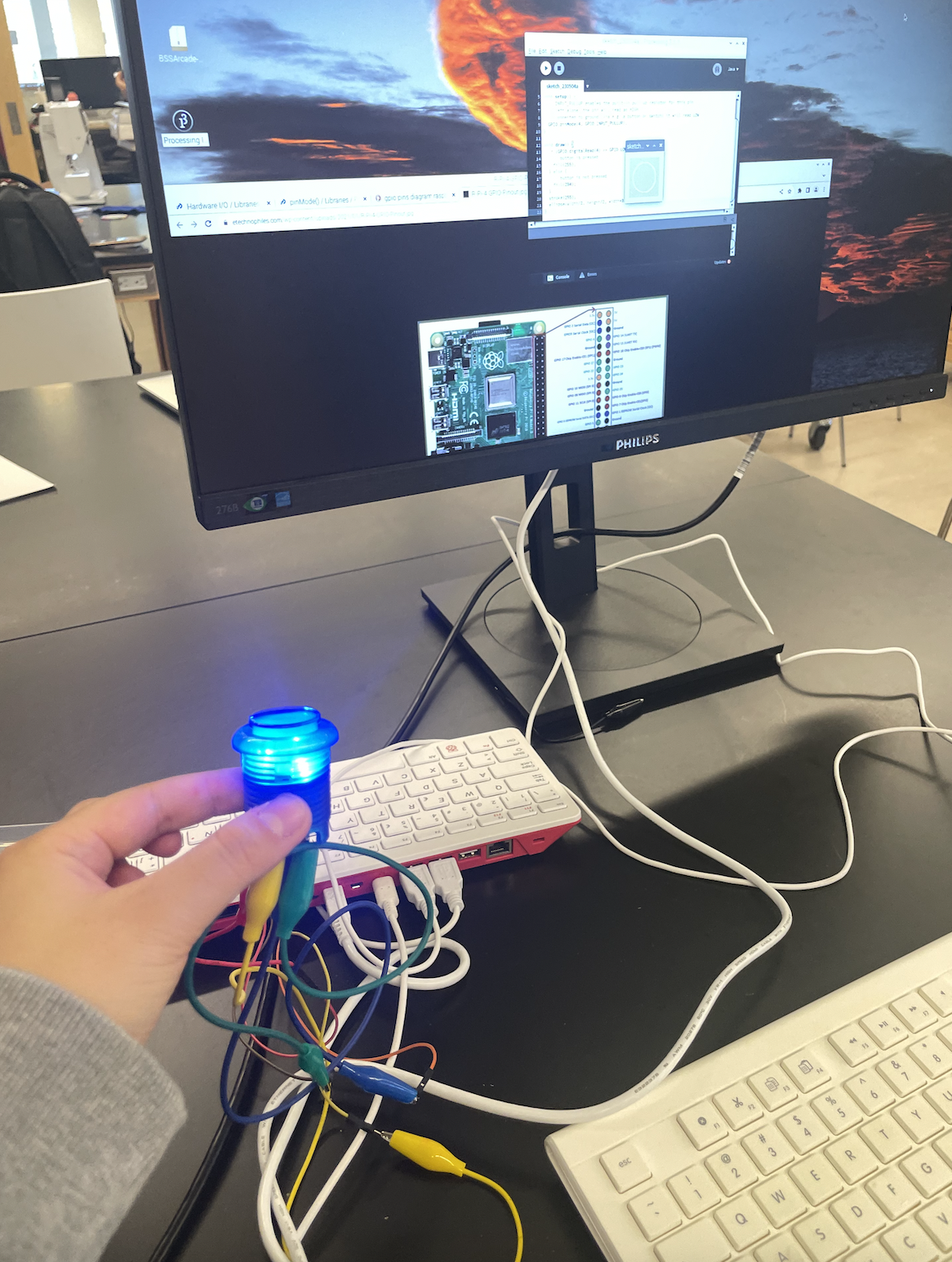

The hardest part wasn't the software, that's intuitive. It was bridging the physical world with the digital one. The arcade buttons and joystick needed to be wired to the Raspberry Pi's GPIO pins, and the Pi I was using was a little unique, as it was also connected to it's own keyboard which had a layout in spanish.

Figuring out how to map those physical voltage changes on the breadboard to the Raspberry Pi’s circuits (specifically the GPIO pins) was tricky due to the lack of documentation on this specific Pi. But after some trial and error, all worked out.

The First Game: "Tomato Catcher"

A console is nothing without a game to play on it. To test the input latency and the physics loop, I began testing my game as I was developing it for my ICS3U (Grade 11 Computer Science) course final project.

I started very simple. Inspired by an ice-cream stacking game I played when I was younger, I began building the logic behind the tracking and falling of coloured pixel projectiles from the sky, and implementing efficient bounding boxes for the mouth contact. After completing this "Tomato Catcher", I expanded it to include fruits (pineapples and tomatoes), lives, scores, powerups (candy that causes a short-duration sugar rush), and a high score system that saved to the SQLite database. Below is the demo of the first edition of the game.

The game development overall was quite fun, and I ran into very few bugs as I had completed more complex games in the past.

Click here to see a short demo!

The most difficult part was actually figuring out how to seamlessly transition between my interface of game selection and leaderboards to all games. To ensure efficiency in memory usage and smooth transitions without allowing viewers to view the Raspbian Operating System , importing each game into one large Processing sketch proved impractical. Instead, I made each game its own separate sketch, and created a separately coded an executable file that was launched from the main arcade interface. Each game was then given a custom file path that the interface could call when a user selected a game to play.

But yikes was this OS difficult to deal with. Raspbian is not exactly the most user-friendly OS, and I ran into many issues with dependencies and libraries not being supported on the Pi's ARM architecture . But, all worked out in the end, and this actually inspired me to start exploring PC building and Linux systems more in depth!

The Finished Build

There were plenty of headaches—specifically dealing with a retro monitor that had horrendous screen tearing—but seeing the first student game boot up via a custom circuit I built myself made it all worth it.

Returning to this post a few years later, I have finally graduated! This arcade continues to store the final video-game projects of the upcoming Grade 11 Computer Science students both inspiring and inviting my peers to attempt the course. I'm happy to see it in the DT lab and play a few games each time I visit.